Scaling digital cross-border trade

Another conference, another set of panels on digital negotiable instruments, interoperability, electronic bills of lading, ebills of exchange, the trade finance gap, the future of supply chain finance and how AI / blockchain will revolutionise trade going forward.

But where's the progress?

Cross-border trade is complicated. The Digital Standards Initiative was set up to help move trade from paper to digital and came up with 36 documents that are involved. We have added another 4 documents to that list (see more here).

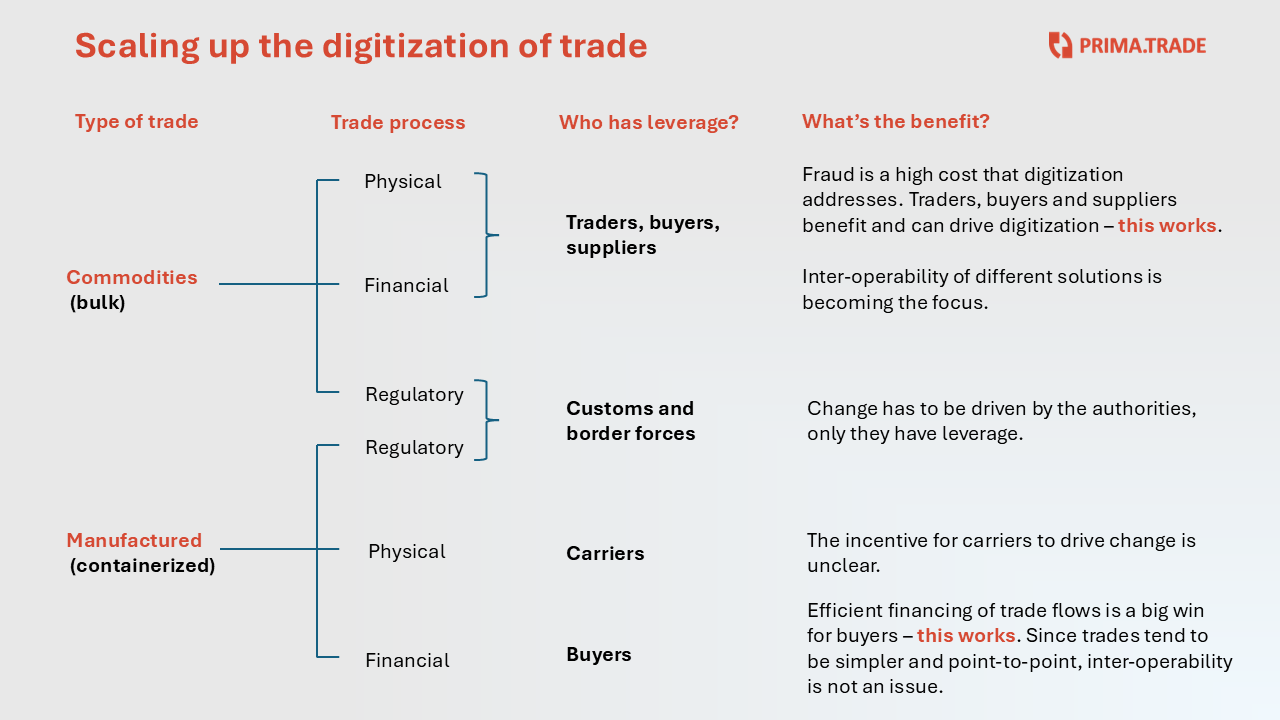

But it's possible to step back from the details and analyse the challenge of digitizing trade via a simple matrix based on:

the two generic types of trade that happen;

the three generic cross-border trade processes;

the three necessary conditions for any given trade process to go digital.

Bear with us - it will all become clear. This is a longer post but if you are interested in trade digitization and how to make it happen - this post is for you!

Two types of trade

These are:

Trade in commodities:

typically shipped in bulk vessels, and often traded as it moves from supplier to ultimate buyer - such as oil and grain,

Trade in manufactured goods:

typically shipped in containers, and often shipped directly from supplier to buyer against a purchase order that the buyer has awarded to the supplier - such as garments, food, machine parts, components etc.

Annual trade in manufactured goods is roughly 2x (by value) the volume of trade in commodities.

Three core processes

There are three generic cross-border trade processes:

Physical:

moving the goods from A to B

Financial:

getting cash to the supplier, potentially allowing the buyer to pay later

Regulatory:

clearing goods across borders from both a duty-payment and a border security point of view.

Three necessary conditions

There are three necessary conditions to be met before a digital cross-border trade process (of any flavour) can scale:

Leverage:

Cross-border trade involves multiple parties; one of the parties has to drive the change and impose a new process on the others - it will not likely happen through some kind of collective decision;

Scalability:

Pilots are one-off trades; converting a pilot concept into an efficient operational environment that works conveniently at scale is a different skill set, and it can even require completely different technology.

Incentive:

There has to be a material benefit to the parties involved, and (in fact) a very clear and substantial benefit has to flow to the party that has the leverage (see first point).

Cracking these three simple factors can convert talk into action.

Who has the leverage? What benefit do they get?

One point to note - there are no financiers in the above table.

Financiers (eg: banks) tend to be reactive rather than driving change here. In the first instance, progress needs to be driven by participants in the trade process itself.

Commodity trade: where are we?

Commodity trade is dominated by some big players.

For example,

the oil majors (eg: Shell, BP, Exxon),

the trading houses (eg: Glencore, Trafigura, Cargill),

some big suppliers and big buyers (eg: BHP, Rio Tinto, Anglo American).

For the purpose of this blog, we can aggregate the traders and the buyers/suppliers into a collective group of "customers".

Although individual trades are complicated with multiple carriers (ie: vessel operators), financiers (ie: banks), counterparties (traders, suppliers, buyers) - collectively it is the "customers" that typically have the leverage because of their scale and influence on the trades that they execute.

Individual customers, where they have wanted to, have been able to drive the adoption of digital processes (eg: data exchanges, electronic bills of lading, digital connections to financiers). They have the power to force the other parties in their trades (including banks and carriers) to work on their selected digital model.

Using paper bills of lading and less robust financial structures has led to many banks pulling out of commodity trade finance. Financial frauds hurt the industry, put up the price of finance and generally lead to lower liquidity. Digitization reduces the fraud risks and makes the processes significantly safer for all the participants.

Scalability of systems is also not so much of a barrier. Commodity trades are large, which means individual financing transactions can justify human attention. So this means that digitization can be brought in from the start without waiting for platforms to operationalize all the processes - although this is now happening with platforms like Komgo, Mitigram and connections into bank back office systems via Finastra etc..

This is already a good start.

It brings with it a problem of "inter-operability". Inter-operability is the capability for data in one party's system to transfer seamlessly and securely to another party's system - but the basic principle that trade should be going digital is getting firmly established across the industry.

The fact that, in commodities trade, we are moving slowly from questions about how to digitize towards questions of inter-operability shows that we are on the way.

Commodity trade: regulatory (crossing the border)

This area is still a work in progress.

Whilst customers have leverage to drive digitization of physical and financial flows, they do not have the leverage to push for trade digitization in customs and border security (ie: regulatory).

We pick this point up again towards the end of the post. - but the key point here is that it is the customs and border authorities that have the leverage and not the customers, carriers or banks.

Containerized trade: more tricky

In containerized trade, we have a much more fragmented picture. There are no dominant customers with the leverage and incentive to drive change.

But analysing who has leverage and incentives shows that there are ways forward

It is fair to say that little progress has been made. But this is how the story can unfold.

Containerized trade: physical processes

Containerized trade is dominated by a handful of carriers - companies like MSC, Maersk, CMA CGM, Cosco etc. The largest four carriers move over 50% of the global flow, and the largest twenty carriers move over 90% of the global flow.

The party with leverage on the physical side is the carrier.

So if we want to digitize the physical flows of containerized goods, we need to focus on the logistics industry and the carriers. No importer, exporter, financier or forwarder has the leverage to require their carrier to use an electronic bill of lading.

Customers (importers and exporters) and financiers (banks) do not have leverage in this area. That's because:

importers and exporters have small volumes individually versus the carriers, and

banks do not take security over the goods in transit when they provide finance - so they have no interest in electronic bills of lading in this area.

But the incentive for carriers to switch to electronic bills of lading is not obvious. They have good revenues from the current paper-based processes which they could lose in a switch to digital.

Cracking how to persuade carriers to adopt electronic bills of lading for containerized trade flows is a work in progress - but this is where the effort needs to be applied.

Containerized trade: financial processes

Most containerized trade flows are not financed by "trade finance". The flows are on open account. We estimate that significantly more than 90% of trade flows are not financed.

The reason why cross-border containerized trade is typically not financed is because buyers find it difficult to approve invoices for payment before delivery. And, in turn, buyers find this difficult because there is no data available to support such a decision.

Digitization can re-introduce trade finance to containerized trade - a big win.

Digitization of trade documents can solve the data problem by enabling buyers to get comprehensive information about shipments as they happen. In turn, this can enable buyers to approve invoices for payment at shipment - leading to the availability of efficient trade finance at scale.

Our clients at PrimaTrade are saving 1-2% on the cost of goods because it is simply more efficient to get exporting suppliers paid quickly using new forms of digital trade finance (eg: "cash against data").

The party with the leverage on the financial side is the importer.

The importer is the party that has to approve the invoice for payment at shipment, and it is the party that will typically coordinate one or more banks to pay the exporting supplier immediately.

The platform required:

extracts data from trade documents at scale at shipment with minimum effort

gets that data efficiently to the buyer for the buyer to approve the invoice

so that a financier can immediately pay the exporter

enabling the buyer to realise a discount on the cost of goods.

Cash against data enables the importer to get a direct benefit from trade digitization

This is exactly what PrimaTrade's "cash against data" technology achieves at scale for importers - this technology is also endorsed by the ICC UK (see more here). This is how to drive digitization of the financial process at scale in containerized trade.

Digitizing trade regulatory processes

The regulatory process involves providing data to customs and border security about the goods in transit to enable them to be checked (as required) and for the right duty to be paid.

Trade digitization provides significant opportunities for efficiencies and better processes:

Efficient data-driven pre-approvals so that goods cross the border more quickly

More accurate duty calculations

Better resource allocation for authorities

Better border security for all of us

But the party with leverage to make digitization happen is the customs and border authority itself.

There are some examples where customs and border authorities have set up digital environments for trade documents - the most well-known being in Egypt. Several other countries are following this model. This underlines the fact that digitization in this area starts with the authorities, not the financiers, traders or importers/exporters.

Our discussions with customs authorities have led us to understand that most of them are reluctant to impose new standalone digital processes on their customers - the importers/exporters moving goods across the border.

A preferred strategy would be to re-use data being created for physical and financial processes. So customs authorities are likely to be late-comers to the digitization process.

PrimaTrade's platform has a role here in containerized trade. Importers and exporters cooperate over the PrimaTrade platform to digitize their trades because of the significant financial wins that result. That same, comprehensive data about the shipment can then be directed towards the customs and border process without creating a new set of digitization activities.

Scaling digital cross-border trade - what next?

This blog post is intended to help the digitization debate move forward.

Digitization of trade will benefit everyone, but making it happen requires a considered approach.

Here at PrimaTrade, our "cash against data" technology provides the solution for one key part of the global trade flow - the financial process. Here the importer has both the leverage and a significant benefit which can enable trades to be digitized at scale. And there is the potential for that same data flow to support more efficient physical and regulatory processes on top.

Digitize once - use the data many times.